When I told you about the Atlantic Islands of Galicia, I told you that in Spain there are several small archipelagos, not very well known, but home to an extraordinary representation of wildlife. It is fascinating to see how in very small territories there can be species that are unique in the world. Today I am going to tell you about another of these tiny archipelagos, but of an importance that far exceeds their minuscule size: the Columbretes Islands.

Volcanoes in the Western Mediterranean

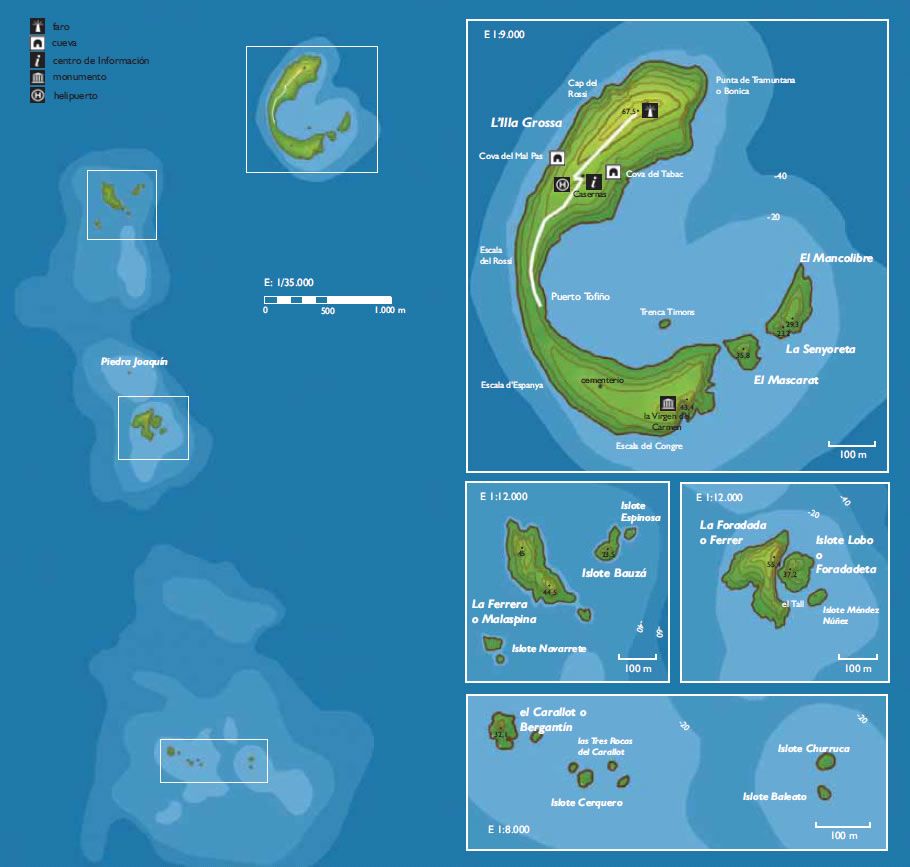

The archipelago of the Columbretes Islands is located in the Western Mediterranean, just fifty kilometres away from the port of Castellón, in the province of the same name in the Valencian Community. It consists of 24 islets divided into four groups, each of which is named after its main islet. From north to south: Columbrete Grande (L’Illa Grossa in Valencian), Perrera (Ferrera), Horadada (Foradada) and El Bergantín (El Carallot). The emerged area occupies 19 hectares.

La Isla Grossa, the big island

As its name indicates, the Isla Grossa is the largest of them all, and the highest of them all, at 67 metres above sea level. This island also clearly shows the volcanic origin of the archipelago, as it has the shape of an almost perfect semi-submerged volcanic caldera, very similar to the famous Greek island of Santorini. The appearance of these islands is parched and cliffy. But appearances are deceptive, and these volcanic islets hold many surprises.

The first of these is their very origin. It is a very unusual example of Quaternary volcanism, whose activity began between three and a million years ago and ended about 30,000 years ago. The islands arise from a volcanic field measuring 90 x 40 kilometres in size, with average depths of 80 to 90 metres. There, as a result of the pressure exerted by the African tectonic plate on the Eurasian plate, a north-south fault arose along which the magma rose, raising the volcanic edifices that make up the Columbretes.

History of the Columbretes.

Snakes and smugglers

These islands are old acquaintances of the Greek and Roman navigators of classical times. This is not surprising, as the Mediterranean held no secrets for them. The islands are named in Strabo’s Geographica (1st century BC), and he gives them the name of Ophiusa Island, because they were infested with poisonous snakes. Two hundred years later, it was Pliny and Mela who spoke of these islands, giving them the name of “Colubrarias Islands”, because the infestation of snakes continued, and from this name derives the current name of “Columbretes”.

When I tell you about the terrestrial fauna of the islands, I will tell you more about these snakes, but for now it is enough to know that they were the decisive factor why the islands remained uninhabited for many centuries, becoming a refuge for pirates, smugglers and outlaws.

As is always the case, it was British seafarers who first paid closer attention to these islands, and in 1823 Royal Navy Captain W.H. Smyth took up his position and published his observations and research in The Journal of the Geographical Society of London in 1831. It was probably on seeing the British interest in this tiny archipelago, but strategically located as an aircraft carrier off the Valencian coast, that the Government of Isabella II decided to organise an act of sovereignty, just in case, and between 1856 and 1860 the lighthouse was built that today crowns the Isla Grossa. To achieve this, the dangerous vipers that infested the islands had to be exterminated. For this purpose, fire and raids carried out by convicts were used extensively. Scorpions, which were also very abundant, were fought by means of the chickens brought by the lighthouse keepers and their families, although they have not been exterminated. The people who tended the lighthouse were the only inhabitants of the island until the time of its automation in 1975.

Illa Foradada

In 1895, the islands were visited by a unique personage: Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Habsburg. Born in what is now Bohemia, he travelled around the Mediterranean making all kinds of scientific and ethnographic observations. Settled in Mallorca, he was the pioneer of tourism in these islands and explored the Columbretes, making the most exhaustive study of them to date. He published his research in the book Las Columbretes, which was published in Prague.

Illa Foradada

Between 1975 and 1982 the islands were used as a firing range for the US and Spanish navies. Such barbarity was contested from the nearby mainland with continuous demonstrations and initiatives to stop this abuse. And finally, in 1988, the Columbretes Islands Natural Park was decreed, managed by the Valencian Community.

Two years later, in 1990, the Marine Reserve was created, managed by the State. This may come as a surprise to you, but this is precisely where one of the most impressive riches lies, not only of the Columbretes, but of all Iberian Nature: the sea beds of the Columbretes are, without doubt, among the richest in the Mediterranean. We will talk about it below.

Situación de las Islas Columbretes

In 1995 the islands were declared a ZEPIM (Special Protection Area of the Mediterranean). At present there is an Integral Marine Reserve zone around the Grossa and Carallot islands, which is not accessible. Visits to the islands are restricted to Grossa Island, which can be reached by hiring private boats (usually belonging to tourist companies) that leave from Castellón. On Grossa Island you can go ashore but under strict rules of behaviour. The rest of the islands can only be seen from the boats, which are forbidden to anchor. We will get to know its fauna, both submarine and terrestrial.

Illa Foradada

Why are these seabeds so extraordinary? Because, on a sedimentary plain (i.e. composed of a substratum originating in erosive materials and/or transported by rivers), the volcanic edifices I mentioned earlier were superimposed. This created a multitude of rock shelters for many types of fauna. In addition to this contrast between a sedimentary and a volcanic environment, there is the barrier effect that these volcanic edifices present by cutting the dominant current in a NE-SW direction, which causes sediments and nutrients to accumulate on the side exposed to the current compared to the opposite side.

Let us characterise what these habitats are like. They occupy two underwater “floors”: the infralittoral (at depths between 0 and 50 metres) and the circalittoral (between 50 and 200 metres). Two types of substrate are defined: rocky, with rocky and “coralligenous” bottoms dominated by invertebrates. The other type of substrate is detrital, composed of organic remains. This substrate has four types of bottoms: maërl (coralligenous algae), gravel/mollusc shells, muddy sands and bottoms with gas upwelling. As you can see, a very rich mix of marine ecosystems.

These seabeds have attracted the attention of specialists due to the absence of Posidonia oceanica meadows, the marine plant that traditionally dominates the Mediterranean seabed. Specialists believe that this is due to the recent formation of these seabeds, for which Posidonia would not yet have had the opportunity to colonise.

Sustratos rocosos

These rocky bottoms are dominated by a zoological type called Cnidarians. This word will sound like Chinese to you, but it won’t be so strange if I tell you that cnidarians are corals and jellyfish in general. Cnidarians are animals that alternate, throughout their lives, two “stages”: a larval stage that navigates freely, and a polyp stage, which attaches itself to a rock or other polyps, develops tentacles around its mouth and eats the food particles carried by the currents. Corals, for example, form their reefs by accumulating the calcified corpses of millions of polyps that have died, on which new polyps develop.

Coral rojo

In the rocky bottoms of the Columbretes we find the red coral Coralium rubrum, which is not excessively abundant. This coral has been the object of economic exploitation since ancient times, and is protected. Another emblematic cnidarian of this area is the gorgonian. Three species are present: the white gorgonian Eunicella singularis, the yellow gorgonian Eunicella cavolinii and, above all, the magnificent red gorgonian Paramuricea clavata, which forms large extensions between 32 and 77 metres deep. This arborescent-looking gorgonian is emblematic of the seabed in the western Mediterranean. It is of considerable ecological value as it provides biomass and structure to these benthic (bottom-dwelling) communities. It is slow-growing and has a long lifespan. It can form monospecific or mixed “forests” with the other two gorgonian species.

Coral rojo

The arborescent sponges Axinella polypoides and Phakelia ventilabrum, as well as brachiopods, polychaete worms, bryozoans, sea urchins and starfish, etc., complete these rocky bottom communities.

There is a group of algae called “calcareous red algae” because they have the particularity of precipitating calcium carbonate in the form of calcite and aragonite crystals. These algae generate an ecosystem called “coral bottom”, also known as the “Mediterranean Garden”. It develops below 20-25 metres depth and up to 200 metres, with subdued lighting and a relatively low and uniform temperature all year round. It can be compared to an underwater subtropical forest, which constitutes one of the most diverse marine habitats in our waters, hosting up to 1,300 animal species.

Detrital substrates,

These are made up of calcareous deposits of dead organisms mixed with sands and/or muds. The so-called maërl beds stand out, composed of accumulations of calcareous red algae that form structures resembling coral reefs. They occur between 30 and 150 metres deep in the Mediterranean. On these seabeds there are large expanses of cnidarians such as Epizoanthus and Poliplumaria, as well as anemones and hydrarians. In this interesting mixture of seabed and marine habitats there are crabs such as Calappa granulata, Dromia personamta and Dardanus calidus. Also of economic and fishing interest are the lobster Homarus gammarus and, above all, the red lobster Palinurus elephas.

Mero,

When the Columbretes Islands were granted protection, the situation of their fauna was deplorable. If pigs, chickens, mice and garden plants had been introduced on the land, the effect of abusive fishing was evident in the marine area. Precisely as a result of the declaration of the Marine Reserve, species such as lobster began to recover in such a way that the Reserve began to behave as a “source” of new population. Although fishing is not allowed in the integral reserve area, fishermen only have to fish for lobster around the islands, which has become a major economic resource. The record catch is a lobster weighing 5 kg.

Sunfish Mola mola

As could not be otherwise, the Ichthyofauna is well represented in the waters of the Columbretes. Pelagic fish include the sardine Sardina pichardus, anchovies Engraulis encrasicolus, the barracuda Sphyraena sphyraena, the lemon fish Seriola dumereli, or the sunfish Mola mola, one of the largest bony fish in the world, which feeds in deep waters on jellyfish, squid and sponges. Only boats using traditional gear such as surface trolling, which is a “string” of hooks rigged in such a way that they glide with the boat at medium depths to catch only pelagic fish, are allowed to fish commercially in the Islands. Gears that damage the bottom, such as trawls and longlines, are prohibited. Some 109 vessels are licensed to fish in these waters.

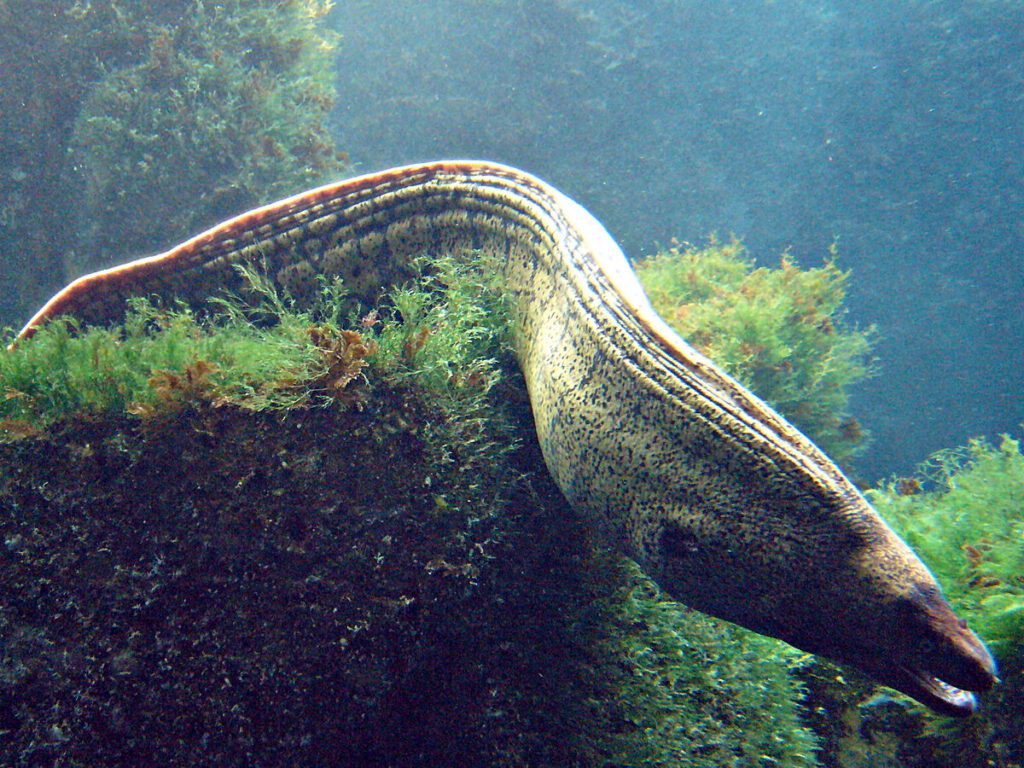

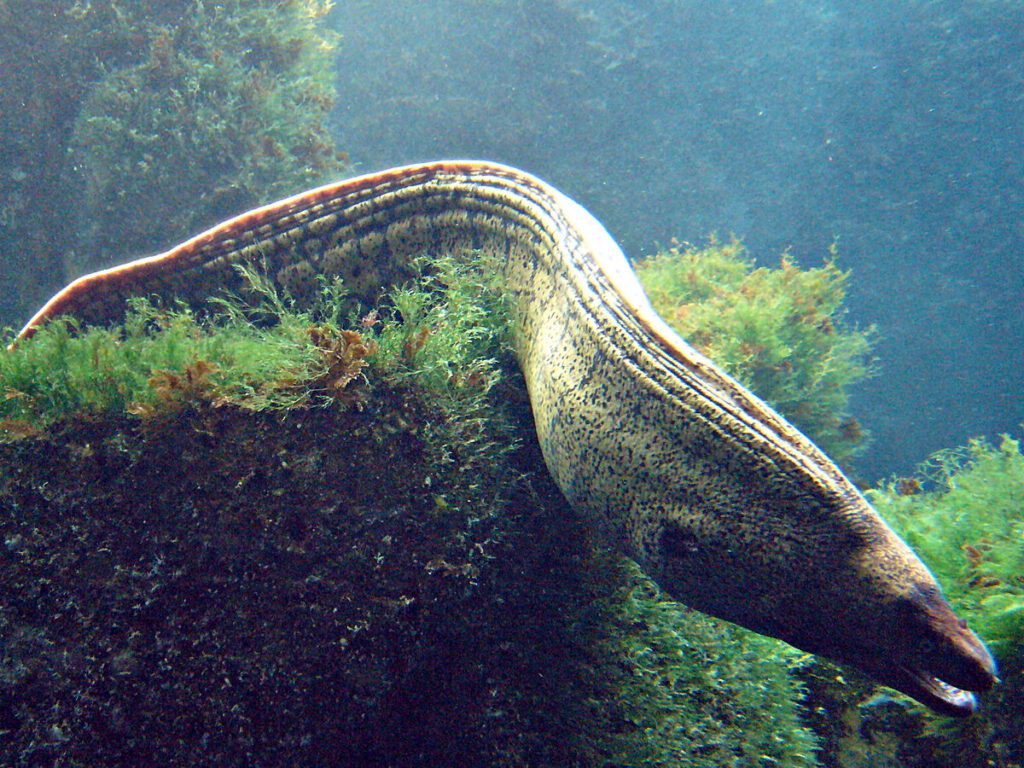

Muraena Mediterráneo

As for benthic fish or, as they are popularly called, “rock fish”, so much appreciated in Mediterranean gastronomy, the presence of the Scorpaena scrofa scorpionfish, the Coris julis damselfish, the red scorpionfish Serranus cabrilla, the chestnut Chromis chromis, the St. Peter’s fish Zeus faber, the shark Diplurus vulgaris, the Mediterranean moray eel Muraena helena, the black croaker Sciaena umbra and the undisputed king of this type of fishing: the grouper Epinephelus marginatus.

The loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta is the most common marine reptile in the Mediterranean. In this area they live on the continental shelf. They are found here all year round between the Integral Reserve and the adjacent areas. Between the Ebro Delta and the Columbretes, some 19,000 turtles have been counted, while in the waters of the Columbretes there are about 1,300.

The cetaceans most commonly observed in these waters are: the striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba, which usually moves at depths of over 200 metres, the bottlenose dolphin Tursiops truncatus, which is found all year round, and the fin whale Balaenoptera physalus, which is usually seen here in March and the first half of April, on its migration towards the more northerly areas of the Gulf of Lion. Unfortunately for the Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus, the protection of these islands came too late: the last specimen in the Columbretes was seen in 1961.

Avifauna de las Columbretes.

It is normal for there to be a great abundance of seabirds on oceanic islands with cliffs, as this topography provides them with an important defence, especially during the breeding season. The Columbretes are no exception to this rule. These small islands are notable for the presence of breeding colonies of two important birds, both endemic to the Mediterranean:

Eleonora’s falco

Eleonora’s falcon Falco eleonorae is named after Eleonor of Arborea, an aristocrat who, in medieval Sardinia, was the first to dictate protection regulations for this falcon. It breeds in various areas of the Mediterranean, almost exclusively on islands, although it can also appear in coastal enclaves during the migration season, as it is a migratory bird that spends the winter in Madagascar, Reunion and Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean. In Spain it breeds only in the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands and the Columbretes, where in 2010 there were 61 pairs, with a moderate upward trend.

The Audouin’s Gull Ichthyaetus audouini is also native to the Mediterranean and some coastal enclaves of the North African Atlantic and southern Iberian Peninsula. In the Columbretes there are about 120 pairs, far from the population that existed here in the 70s and 80s, when it was more endangered than today.

Avifauna de las Columbretes.

Other birds present in the Columbretes, including residents, migratory and passing birds, are the Cory’s shearwater Calonectis diomedea, which breeds in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and winters in the South Atlantic. There are about 55 pairs in Columbretes. Also, the European storm petrel Hydrobates pelagicus, the Mediterranean shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii, the Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus, the Mediterranean shearwater P. yelkouani, or the dwarf gull Larus minutus, among many others.

Terrestrial fauna

When you look at these parched volcanic crags it may seem incredible that they are home to any kind of terrestrial fauna. Well, there is. Life is making its way, and I have already explained how oceanic islands are populated. Air currents bring spores and plant seeds that eventually take root, fertilised by the nitrogen of seabirds seeking calm and shelter for breeding. The air, and also the feet of birds, bring insects. And, sooner or later, terrestrial vertebrates arrive, usually carried by currents, on logs or floating vegetation.

This is probably how the snakes that gave them their name came to the Columbretes Islands. The neighbouring Levantine coast is devastated every year by torrential rains that fill the parched wadis with impetuous floods that carry a great deal of detritus and vegetation out to sea. The Ebro Delta, for its part, contributes in equal measure to this potential supply of castaways.

Although the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid houses a specimen of the snakes that were eradicated on the islands, it has not been possible to identify which species or species they were, because the origin of the specimen is doubtful. It is thought most likely to be the snub-nosed viper Vipera latastei, which is endemic to the Iberian Peninsula.

What could this swarm of snakes have been feeding on? They would probably prey on the seabirds that frequented, and still frequent, the archipelago. It is also likely that cannibalism played a role, as is the case with the other endemic reptile of the Columbretes: the Columbretes lizard (or sargantana, as it is called in Valencian), Podarcis atrata, undoubtedly related to the Iberian lizards.

There are four isolated populations of lizards in the archipelago, on different islets, especially on Grossa Island. Although these lizards have many insects to eat, there is a high rate of cannibalism: adult lizards prey on eggs and young.

Columbretes Sargantana

Earlier I mentioned the large number of scorpions that still remain on the islands. They belong to the species Buthus occitanus, the most common on the neighbouring continent, so we can think that their accidental arrival on the Columbretes is relatively recent and they have not yet had time to evolve in isolation to generate the corresponding endemism. There is also a rich entomofauna, but I will highlight the 10 species of insects endemic to the Columbretes, most of which are tenebrionid beetles, such as Alphasida bonacherai or Tentyria pazi. Tenebrionidae are a family of black beetles, specialised in feeding on detritus, and very typical of arid and steppe areas, so it would not be unreasonable to suppose a North African origin for them. Other Tenebrionidae present on the islands are: Pimelia interjecta, Scaurus vicinus, Scaurus rugulosus, Blaps gigas or Blaps lusitanica. There are also mealybugs (Isopods) such as Armadillo officinalis.

Even the Columbretes have an endemic snail: Trochoidea molinae.

Once again, realise the faunistic importance of the islands, however small they may be. Humble, ugly, parched, forgotten and unknown, the Columbretes offer the richest seabed in the Mediterranean, and a small terrestrial fauna, but with many endemic species not found anywhere else in the world.

Gracias

Con el permiso y el agradecimiento de

Eugenio Fernández Sánchez

https://www.linkedin.com/in/eugenio-fernández-sánchez-086964160/